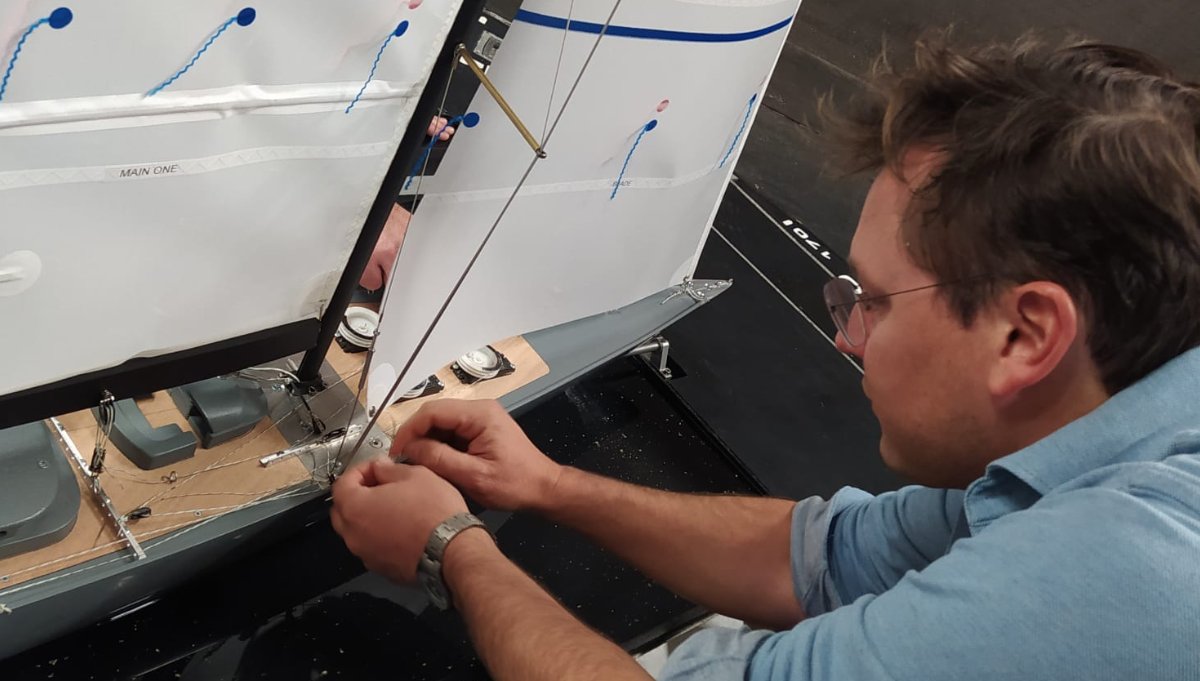

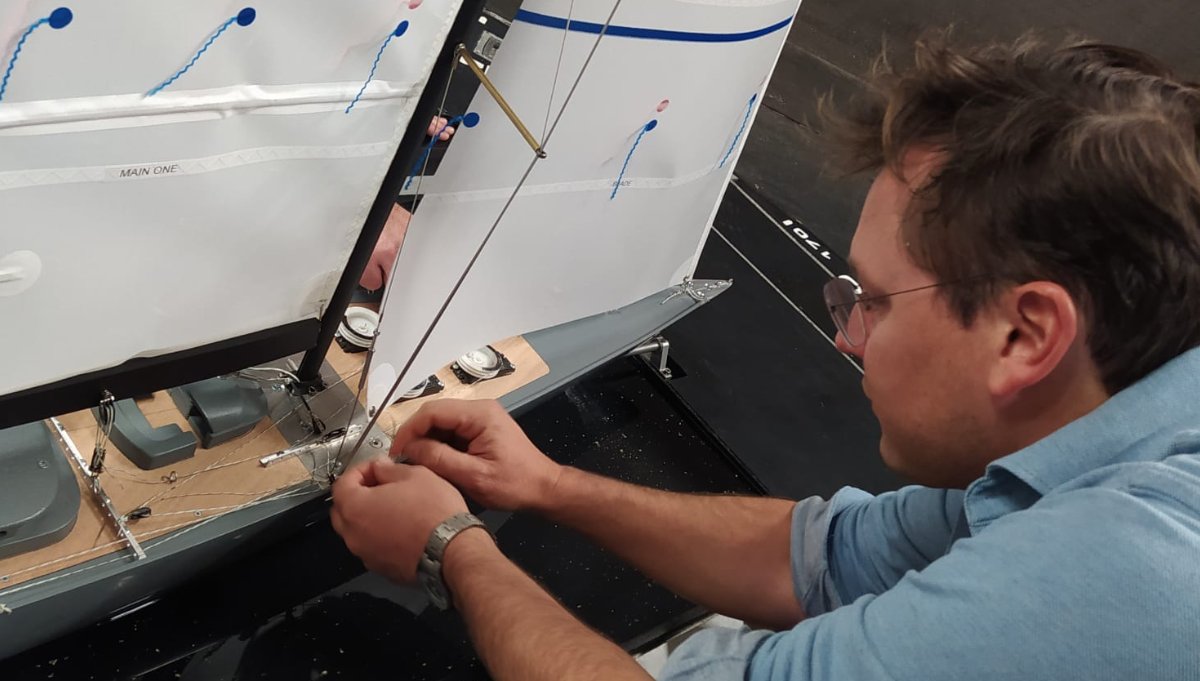

Mark Leslie-Miller Wind Tunnel Testing Project Zero

Mark Leslie-Miller Wind Tunnel Testing Project Zero

A day in the life of a naval architect

Mark Leslie-Miller of Dykstra explains how his dual passions for technology and sailing make naval architecture the perfect career for him.

To admire a superyacht as it sails majestically across the water is to see a gleaming finished product, a fait accompli. We might be curious about where it’s sailing to, who owns it or even who is captaining it, but less frequently do we consider how it all came together. If we did, we might find a naval architect, like Mark Leslie-Miller, somewhere near the starting line.

Leslie Miller is a partner at Dykstra Naval Architects – a Dutch firm founded by Gerard Dijkstra back in 1969. The company has broken boundaries in yachting – with recent projects including the futuristic SY Black Pearl, Sea Eagle and Sailing Yacht A. Naval architecture firms like Dykstra are often the first port of call for clients and owners who have a concept in mind for their next yacht. “The moment a client decides to design a yacht is the moment we step in,” says Mark. “We are usually involved from the get go.”

Dykstra Naval Architects Team Photo: Jolanda van der Linden

Dykstra Naval Architects Team Photo: Jolanda van der Linden

From a dream to reality

So, what is the starting point for a project of such mammoth proportions? Mark explains; “First off, we chat with the client and from that, we’ll put together a design brief. We’ll make a sketch design to see whether we’ve got the general idea right, then we enter into the design and optimisation phase, where we find the right balance in the design to meet the client’s expectations.” The next step is to work towards a contract design with the client or a shipyard.

Mark relishes the opportunity that naval architecture gives him to blend his dual passions for technology and sailing. “My job is very tech-led and challenging in terms of the calculations that go hand-in-hand with it,’ says Mark. “We need to work in big teams with people from different parts of the industry – from the shipyard to the systems engineers. But we also work directly with clients whose hobby is to build sailboats so it’s generally a very happy and hobby-oriented atmosphere,” says Mark.

In terms of tech, there are some basic naval architecture skills that every yacht requires: stability needs to be sufficient for the sail and the hull needs to provide that stability, yet have as little drag through the water as possible. “That’s the bread and butter of naval architecture,” explains Mark. “But for a lot of the projects we work with – clients want something very special that pushes boundaries far beyond that.”

Project Zero entering shed Photo: Tom van Oossanen

Project Zero entering shed Photo: Tom van Oossanen

Going beyond the norm

Sailing Yacht A is an example of such a boundary-pushing yacht. “Everything on this boat was too big to handle manually so we needed to design an automated smart system that allowed you to manage these huge rig-loads in a safe way.” Project Zero – a zero fossil fuel yacht currently in build – is another example. “This one is more about energy-saving systems – hydrogeneration and voyage planning,” says Mark.

“When we’re stretching the limits of what can be done we need to make sure that it can actually be achieved successfully during the materialisation of the yacht,” says Mark. That means that during the realisation phase where the shipyard does more engineering and more work, the naval architect stays involved to guard the original philosophy behind the yacht.

SEA EAGLE Photo: Tim McKenna

SEA EAGLE Photo: Tim McKenna

Celebrating a job well done

Happily, the role of the naval architect involves time spent on the water too. “During the commissioning phase we’ll often do some sail trials and sometimes we go along on the maiden voyage and make sure it’s all as we intended,” says Mark. And it doesn’t end there. “Luckily we get invited by quite a few owners to go to sail regattas with them in places like St Barths or the Mediterranean. That’s nice – I think it’s important to get on the water with these boats every now and then, there is no better alternative to hands-on experience.”

So what is Mark’s advice for anyone wanting to become a naval architect? “In the past, the world of yacht design was dominated by self-made men who learned the required naval architecture skills on the go, but nowadays a proper scientific education is a big bonus” says Mark, who studied at Delft University. “I think being able to understand the passion of being on the water is also key. I’ve been a sailing enthusiast all my life. It’s difficult to imagine a lot of the things we’re working on if you’ve never been in that situation. So being an actual sailor and knowing the enjoyment that comes from being on the water is super important.”